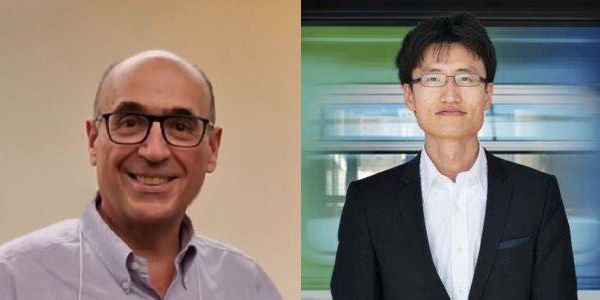

Fundamental changes to how we work and commute have forced public transit agencies to contend with a new normal after the Covid-19 pandemic. Jim Aloisi and Jinhua Zhao of MIT's Transit Lab propose a way forward.

QUESTION 1: What technology or technologies are the focus of your research, teaching, and action?

Jim

Our work addresses transit in a broad range of contexts. We are currently focusing particularly on urban transit recovery in the post-pandemic environment as transit adapts to a “new normal.” This research intersects with the future of work and considers how people are working remotely. Are people working more flexibly? Who are the individuals who must still show up at work or prefer to do that. Our work asks what the implications of these shifts within work are for transit recovery when you have a transit system that is highly dependent on fare revenue for operating expenses. There appears to be a potentially permanent gap between current and pre-pandemic ridership. We are leveraging surveys to collect data and understand riders’ attitudes to consider what do workers think? What do prospective workers think? Rider attitudes and preferences will inform whether they continue to use transit, and if they do continue to use transit, we aim to understand how their journey patterns change. On the worker side, you have a nationwide workforce shortage in transit. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a massive resignation or retirement of transit workers. Agencies are finding it very difficult to replace those workers in a low unemployment economy, at a time when those jobs may not be viewed by people as particularly attractive, notably by particularly younger people. For this reason, our lab is exploring ways to leverage technology to optimize transit worker labor. If you think about a potentially longer term reduced workforce, you might want to think about introducing technology to their work in ways that optimize and make them more productive, but also in ways that make them more interested in the work they're doing.

Jinhua

Let’s use another example. Public transit is almost biased in nature because it is already in the public interest. It's called public transit because it responds directly to major societal issues such as equity, climate change, and public health through the lens of transportation. One thing we've been discussing recently is the change in expectations about public transit, as well as the change in the expectations of transit workers. In Los Angeles, or in Washington DC, there are trends indicating that people who use drugs, who are unhoused, who have mental health issues increasingly find refuge in transit infrastructure, from vehicles to stations. Now the question is: Can transportation laborers, bus drivers, and others gain skills to help this group of people and thus add a component of social work to their role in a public agency. In other words, how do you transform these jobs so that public transit employees can help this group of people who are also part of the transit ecosystem?

QUESTION 2: What are the ways in which these technologies are and could be used to advance the public interest?

Jim

When considering the future of work and understanding both attitudes and behaviors that will influence a variety of factors going forward in public transit, we must also believe it is possible to achieve carbon emission reduction goals through encouraging more people to ride transit and rail. Despite an increasing transition to electric vehicles (EVs), they continue to have many of the negative externalities of auto mobility, including particulate matter emissions, and how we will govern the carbon-intensive infrastructure associated with supporting electric vehicles: regular charging stations, highway and road pavement, constructing parking lots. Post-pandemic transit recovery and adaptation to a new norm influenced and informed by technology is critical not just to that industry, but to sustainability overall. This requires not just reducing emissions, but making urban environments healthier places.

Jinhua

When studying future technologies like autonomous vehicles (AVs), the contrast of public and private interest is increasingly important to consider. These new technologies can easily, and by default, serve the private interests of the company developing vehicles to sell to individuals who can afford this new product. And that’s typical of new technology. In this case, the public interest perspective becomes increasingly critical because the technology will come, and we need to ask how we—as researchers, practitioners, and policymakers—can guide industry to serve rather than compete with public transit and mobility needs. This requires both technical thinking on how to schedule both public transit and autonomous vehicles together offline, but also policy thinking on how to design the policy to induce AV manufacturers and operators to behave positively.

Jim

Concerning optimization, someone in our lab is working on developing a model to help agencies optimize overnight work in subways. This may seem like a mundane issue, but in older urban subway systems like the MBTA in Boston, WMATA in Washington DC, CTA in Chicago, and MTA in New York, agencies only get to work on signals, electric systems, and rails when the service is not running overnight (if they don't have 24-hour service). Optimizing each move is important not just for agency productivity, but for overall rider experience.

QUESTION 3: What more could be done to ensure that these technologies are designed, used, or regulated to better address the needs of those at the margins of society?

Jim

A unique feature of the Transit Lab is that it works closely with public agencies. We have a built-in test bed environment to pilot ideas researchers are developing. For example, we have started a bus route in Chicago that pilots modeling strategies to optimize service delivery that would overcome the limitations of having a smaller post-pandemic workforce. Through this pilot, members of the lab worked with the agency to pilot the idea for a short period of time on a key bus route. Then you can collect the data, analyze it, determine the efficacy of what you've done, and determine how to scale that process. We think about the intersection of policy, law, and technology; the work we do is rooted and centered in notions of transport justice. Everything we do ultimately is designed to ensure the benefit of transit riders, and transit riders are disproportionately people who come from vulnerable communities.

Jinhua

When we design a research project, we co-define that research question between MIT and the agency from the very beginning. We designed the definition of the question with the agency in order to represent the public interest. We have constant interaction between researchers, students, and staff in the agency. There is constant communication to expose both the research and agency sides to what the agents are thinking, what the passengers want, what the neighborhood wants. This fundamental question of public interest is thus at the heart of our research.

Students trained at MIT’s Transit Lab, whether they go to the public sector or the private sector, have an intuition to ask these public interest questions. Yet we consistently wonder, can MIT training generate a sense of responsibility or just an intuition? What does this policy or technology mean for regular people? What does it mean for carbon [emissions]? What does it mean for society? If there are enough people who continually ask these kinds of questions, they're more likely to generate a cultural change. The corporation will care about it as well. In our lab, we naturally emphasize this question of public interest and public technology, but the question is for the rest of the Institute. Do students receiving training in technology get enough exposure and education on the public interest?

Jinhua Zhao is the Edward and Joyce Linde Associate Professor of City and Transportation Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Prof. Zhao brings behavioral science and transportation technology together to shape travel behavior, design mobility systems, and reform urban policies. He develops methods to sense, predict, nudge, and regulate travel behavior and designs multimodal mobility systems that integrate autonomous vehicles, shared mobility, and public transport. Prof. Zhao directs the JTL Urban Mobility Lab and the Transit Lab at MIT and leads long-term research collaborations between MIT and major transportation authorities and operators worldwide, including London, Chicago, and Hong Kong. Prof. Zhao founded and directs the MIT Mobility Initiative.

Jim Aloisi is a Boston-based lecturer, writer, transit advocate, and strategic consultant. Jim was a partner at two prominent Boston law firms, Hill & Barlow and Goulston & Storrs, where he led a Public Law & Policy practice. He played a central role in the creation of Boston's Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. In addition to serving as Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation in the Administration of Governor Deval Patrick, Jim's public service includes service on the Boston Human Rights Commission, the Massachusetts Transportation Finance Commission, and the Massachusetts Port Authority Board. As Massachusetts Transportation Secretary, Jim guided a landmark transportation reform and restructuring initiative and authorized a pioneering effort to release a complete MBTA data set at no cost to improve transparency and encourage the development of web-based and mobile applications. Jim is the author of four books, including The Big Dig, The Vidal Lecture, and Massport at 60, and is a regular contributor to Commonwealth Magazine. He serves on the Board of TransitMatters, a Boston based transit advocacy group. Jim teaches a graduate course in Transportation Policy and Planning.